Following on from my last post, I want to talk about the issue of referring to certain types of foods as “carbs”. The pervading sentiment in our society is that foods are either “carbs”, “protein”, or “fats”. You know how it goes, meat = protein, rice = carbs, nuts = fats, etc.

This notion might seem like a plausible way of classing these foods, as it is true that these foods have each macronutrient mentioned as their primary constituent in terms of energy. It is my view however that this use of language can cause confusion and potential harm. Let me explain by using “carbs” as an example.

What are carbohydrates?

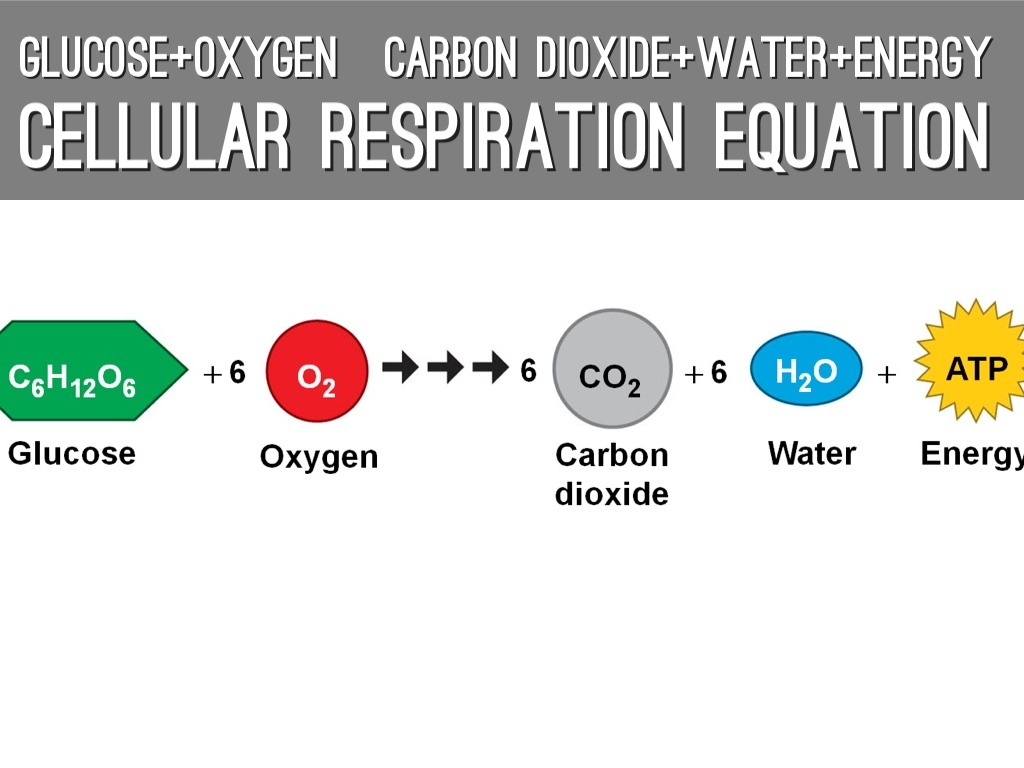

On a basic level, carbohydrates are molecules made up of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen and are the body’s preferred fuel source for providing energy.

All carbohydrates are broken down into single sugar molecules called glucose, which are used by every single cell in our body for energy. Our mitochondria (energy powerhouses of our cells) convert glucose into adenosine tri-phosphate (ATP) which is a unit of energy we need to power our bodily functions (movement, digestion, etc.).

*Fun fact: our brains alone use about 20% of our glucose-derived energy to fuel itself (1).

Types of carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are generally classified as either “simple”, or “complex”. The classification is determined by the amount of chains of sugar molecules strung together, with complex carbohydrates consisting of long, complicated chains, and simple carbohydrates consisting of very few of these chains.

This in turn affects how your body metabolizes these carbohydrates for energy. Complex carbohydrates break down much more slowly than simple carbohydrates, providing a sustained release of energy over time.

Differences between types of carbohydrates

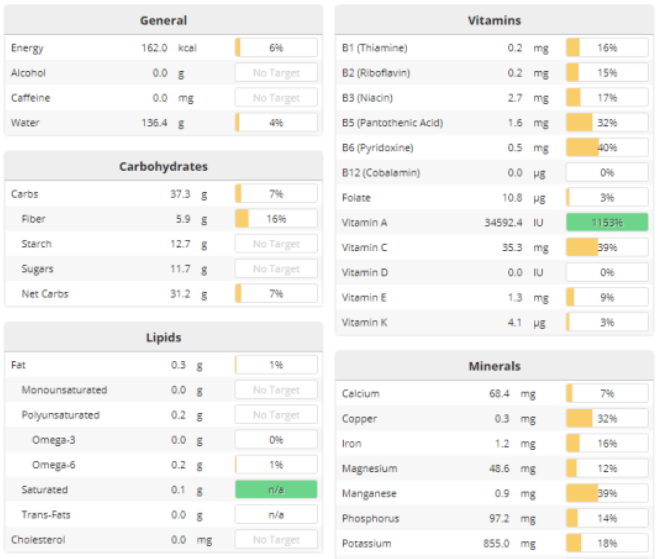

Let’s take a complex-carbohydrate-rich food such as a sweet potato and compare it to refined table sugar. As you can see in the graphics below, one baked sweet potato provides a lot of nutrients, exceeding your daily vitamin A needs (in the form of beta-carotene), providing you with roughly 6 grams of fibre, giving nearly half of your daily needs of some B vitamins and minerals like copper and manganese, and a host of other nutrients. Compare that to an equivalent quantity of calories in the form of sugar: it gives you very little from a nutritional standpoint.

When foods are simply reduced to being “carbs” or not, we run into issues. This logic would entail that sweet potatoes and refined table sugar are the same, as they are both “carbs”. This reductionist classification clearly misrepresents the health value of foods, and may lead people to steer clear of foods like sweet potatoes out of fear that they may become fat or unhealthy because they have heard that “carbs” make you fat.

Takeaway point

Whether a food shares a similar proportion of carbohydrate as another food doesn’t tell us much about its healthfulness.

Misclassification of foods

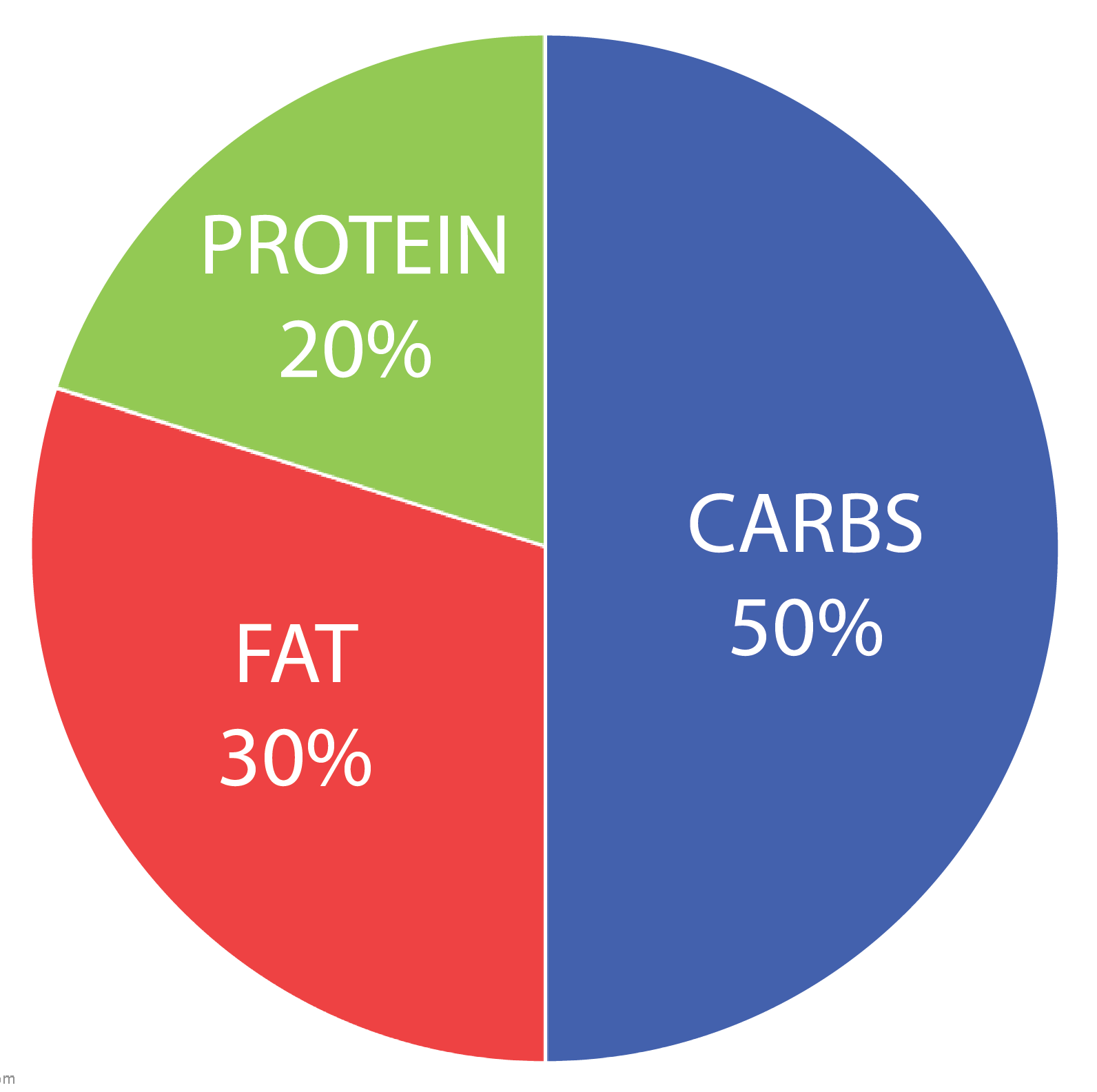

Another issue is that often, people call foods “carbs” when carbohydrate isn’t even the biggest contributor to calories in these foods. Take a donut for example.

You will hear people say that eating “high-carb” donuts will make you fat. Sure, habitually eating ultra-processed foods like donuts may increase body fat levels, but is it because “carbs”?

Take a look at the graphic below. This graphic illustrates how foods that are deemed as “carbs” are often more “fat” than “carbs”. In this example, just 45% of the caloric density of the donut comes from carbohydrates (type in “donut” on the website Cronometer, and you will see that most branded donuts are more fat as a % of calories than carbohydrate).

Do carbs make you fat?

Spoiler alert: they are not uniquely fattening. Overeating calories makes you fat, irrespective of the macronutrient split.

When carbohydrate intake is severely restricted in the body, short-term weight loss is common, and this weight loss is often confused with fat loss. The majority of initial weight loss is actually your muscle carbohydrate stores (glycogen) diminishing, and the subsequent water that is held within glycogen being released (glycogen holds about 3-4 times its volume of water) (2).

A randomized, controlled, metabolic ward experiment from Kevin Hall et al. (2015) put obese individuals on two calorie-restricted, weight-loss diets: one diet was restricting carbohydrate intake, and the other restricted dietary fat intake by the same quantity of calories, while holding protein constant (3).

The research question asked whether fat loss will be the same if both diets are equal in calories, but one cuts carbohydrate and the other cuts fat, or would fat loss be greater for the carbohydrate-restricted diet, like low-carb zealots would lead you to believe? Let’s find out.

Study design

19 obese men and women were randomized to either the reduced-carbohydrate diet (29% carbohydrate, 50% fat) or the reduced-fat diet (8% fat, 71% carbohydrate) for 6 days, after consuming an identical weight-maintenance baseline diet for 5 days. The diets restricted calories by approximately 30% from the baseline diet. This was a metabolic ward experiment so all meals were provided and food intake was supervised, strengthening the results by improving internal validity.

Both diets decreased calorie intake by an average of 810 calories per day, but in the carbohydrate-restricted diet, sleeping metabolic rate and 24-hour energy expenditure were significantly reduced by about 86 calories per day and 98 calories per day, respectively. This was not seen in the fat-restricted diet. Basically, this means that the metabolic advantage (i.e., increased metabolic rate or higher fat burn) proposed by low-carb advocates when restricting carbohydrates was not found in this cohort.

Body weight or body fat?

In terms of body weight, the reduced-carbohydrate diet lost significantly more weight than the reduced-fat diet. Wait, does this prove that restricting carbohydrates does indeed offer an advantage for fat loss? Not so fast… weight loss does not necessarily mean fat loss.

In contrast, the reduced-fat diet showed an average steady loss of 89 grams of fat per day whereas the reduced-carbohydrate diet averaged a loss of 53 grams of fat per day—this was a statistically significant difference. This finding is very important, and showed a slight metabolic advantage to consuming higher carbohydrate and lower fat vs. lower carbohydrate and higher fat (3).

Why might this be?

In order for carbohydrates to be stored as fat in our body, they must undergo a process called de novo lipogenesis. This is the name given to the synthesis of fatty acids from carbohydrate. The body does not like to do this because it is a very inefficient process—when dietary carbohydrate is converted to fat, it costs about 23% of the original calories from carbohydrate in order to do this, compared to storing dietary fatty acids as adipose tissue (fat) which uses only 3% of the original calories (4).

Our body prefers to store excess carbohydrate as muscle glycogen, so once our glycogen stores are full, our metabolic rate increases to burn off this excess carbohydrate. This has been shown in studies where high-carbohydrate meals increase the post-meal burn (thermic effect of food) and therefore increase our own calorie-burning abilities through an increased metabolic rate (5,6).

High-fibre diets have also been proposed as methods to increase metabolism, due to the increased energy expenditure in digestion, and fibre is a type of carbohydrate only present in plants.

One study put overweight/obese people on a plant-based (vegan) diet vs. a National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) diet for 14 weeks, and found a significant increase in resting metabolic rate in the plant-based group vs. NCEP diet group, as well as a higher thermic effect of food in the plant-based group (7).

Increased fibre consumption may help to explain the findings: consumption increased from 21 to 30 g/d in the plant-based group, whereas the NCEP group increased fibre from 19 g/d to 21 g/d only—a highly significant difference.

Weight loss was also significantly greater in the plant-based group vs. the NCEP diet group, even though the plant-based diet was ~75% carbohydrate! Why? Because these healthy carbohydrate-rich foods (beans, lentils, whole-grains, starches, fruits, vegetables, etc.) are extremely healthful, full of fibre, and do not make you fat!

Conclusion

I hope you come away from this post with a greater understanding of why classifying foods as a specific macronutrient (in this case, “carbs”) can lead to confusion.

Carbohydrate-rich foods (beans, lentils, sweet potatoes/regular potatoes, fruit, vegetables, etc.) can be extremely health-promoting and are part of a healthy diet.

Challenge

Challenge for the week ahead: Incorporate at least one serving of legumes into your diet for each day this week. That could be hummus on your whole-grain bread for Monday, baked beans on your toast for Tuesday, black beans in your burrito on Wednesday, or whatever your heart desires.

Have a good week!

References

(1) Mergenthaler et al. (2013). Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900881/

(2) Olsson and Salton (1970). Variation in Total Body Water with Muscle Glycogen Changes in Man. URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1970.tb04764.x

(3) Hall et al. (2015). Calorie for calorie, dietary fat restriction results in more body fat loss than carbohydrate restriction in people with obesity. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4603544/

(4) Sims and Danforth (1987). Expenditure and Storage of Energy in Man. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC424278/pdf/jcinvest00115-0007.pdf

(5) Bowden and McMurray (2000). Effects of Training Status on the Metabolic Responses to High Carbohydrate and High Fat Meals. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12592707_Effects_of_Training_Status_on_the_Metabolic_Responses_to_High_Carbohydrate_and_High_Fat_Meals

(6) Nagai et al. (2005). Metabolic Responses to High-Fat or Low-Fat Meals and Association with Sympathetic Nervous System Activity in Healthy Young Men. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7378237_Metabolic_Responses_to_High-Fat_or_Low-Fat_Meals_and_Association_with_Sympathetic_Nervous_System_Activity_in_Healthy_Young_Men

(7) Barnard et al. (2005). The effects of a low-fat, plant-based dietary intervention on body weight, metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16164885